Common myna (Acridotheres tristis), one of the most invasive bird species in the world.

When common mynas (Acridotheres tristis) were introduced to Mauritius and Reunion island in the 18th century, it was one of the world’s first attempts at biological pest control. However, they have since become pests themselves. They are native in Central to Southeast Asia and have been introduced — both accidentally and on purpose — in many locations across the world, and are especially a problem in small tropical islands with high levels of endemism. They are now one of the most invasive birds in the world.

Map of common myna distribution. Distribution data from BirdLife International and Handbook of the Birds of the World (2016)¹

Early molecular studies using allozymes illustrated the loss of genetic diversity through invasion bottlenecks²⁻³, and Ewart et al. (2019) have investigated the population genetics of mynas in Australia using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data from over 400 individuals⁴. However, our extensive sampling with additional samples from India, New Zealand, Hawaii, Fiji, and South Africa (samples provided by Royal Ontario Museum and generous contributors in New Zealand), in addition to existing data from the aforementioned study, allowed, for the first time, the inference of the origin of invasive myna populations in New Zealand, Australia, Fiji, Hawaii and South Africa, providing an independent finding to existing historical records.

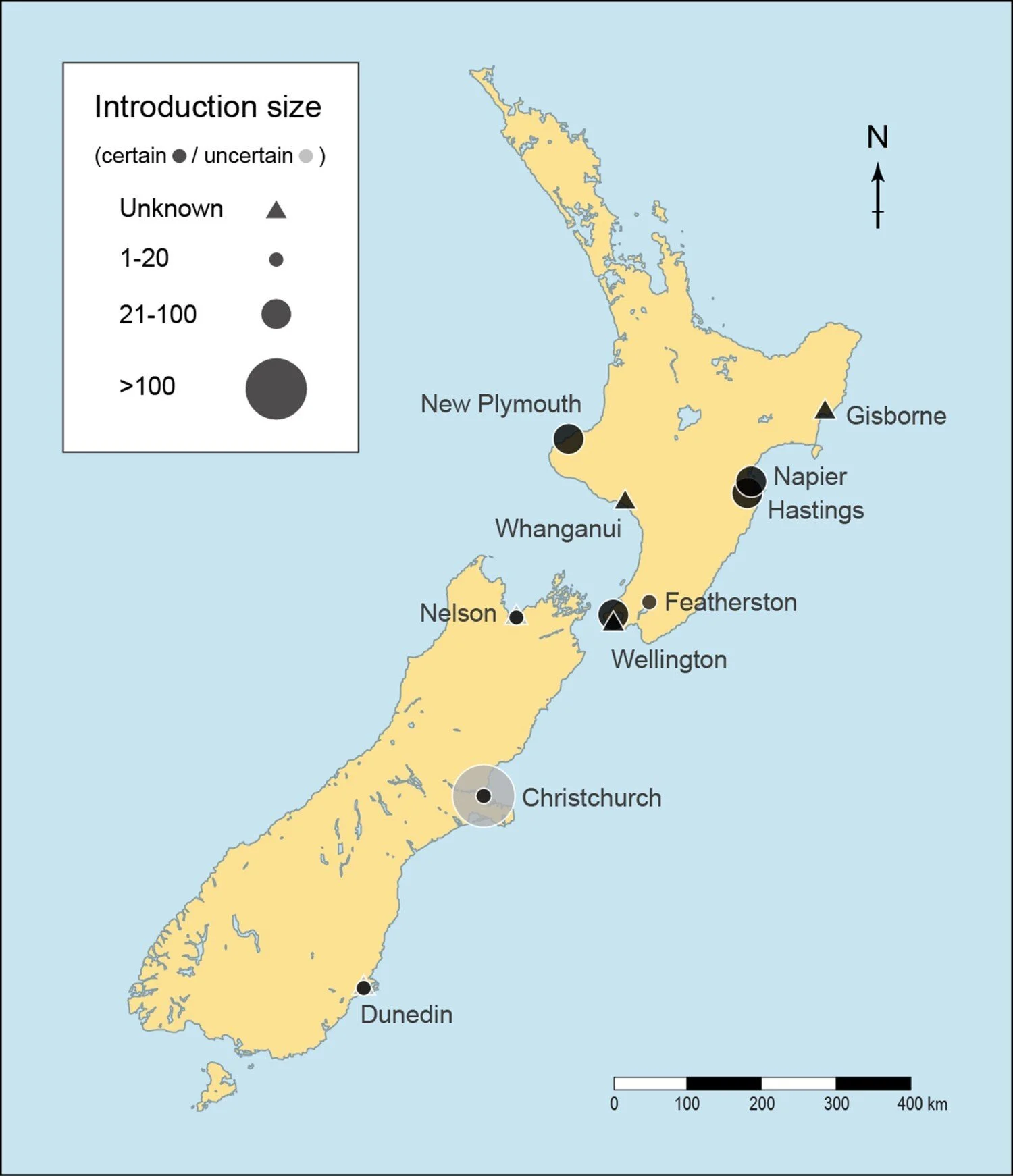

Mynas in New Zealand had a peculiar introduction history. Acclimatisation societies introduced mynas in cities in the South and North Island of New Zealand in the 1870s and 1880s, but mynas are no longer found in the South Island. In the North Island mynas are no longer found in some of the cities where they were originally introduced. Mynas are now most common in the northern part of the North Island (e.g. Auckland, Whangārei) where they were never introduced⁵. It was previously unclear which of the initial introductions to New Zealand survived and formed the current populations. Using SNP data, we identify the population structure in New Zealand, and trace their introduction history, especially of populations relevant to New Zealand.

Locations of introduction of mynas to New Zealand (1868–1883). Map from from Beesley et al. (2023)⁵

We found that mynas in New Zealand are divided into two populations by New Zealand’s North Island Axial Mountain range. The population to the east of the mountain range occupies a smaller range but is more genetically diverse than the population to the west of the mountain range, and this is likely due to the introduction history. The eastern population was founded by birds introduced to Napier where they quickly established. The western population was founded by birds which had moved northwards to more warmer climates, from their initial introduction points in colder cities (New Plymouth, Whanganui, or Wellington).

Based on population structure analyses, genetic differentiation, and patterns of genetic diversity, we found that mynas in New Zealand were likely founded by mynas from Melbourne, which in turn were likely founded by birds from a subpopulation in Maharashtra in India. Mynas in Sydney were also likely founded by mynas from Melbourne and the Sydney population is even more bottlenecked than the populations in New Zealand. Mynas in Fiji were also likely founded by the same birds that founded the Melbourne population, while, interestingly, mynas in Hawaii and South Africa were likely founded by a different source from the native range.

Principal component analysis plot based on 5037 SNPs of mynas from New Zealand and respective sampling locations overlaid with myna distribution in New Zealand.

Our paper clarified the common myna’s introduction history and demonstrated the value of historical archives – both as museum specimens and historical records. With the population structure and introduction history clarified, we can now investigate their genomes further to help answer the big question, why are mynas such successful invaders?

References

BirdLife International and Handbook of the Birds of the World (2016) Acridotheres tristis (spatial data). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Version 2021-3 https://www.iucnredlist.org

Baker AJ, Moeed A (1987) Rapid genetic differentiation and founder effect in colonizing populations of common mynas (Acridotheres tristis). Evolution 41:525–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1987.tb05823.x

Fleischer RC, Williams RN, Baker AJ (1991) Genetic variation within and among populations of the common myna (Acridotheres tristis) in Hawaii. Journal of Heredity 82:205–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111066

Ewart KM, Griffin AS, Johnson RN, Kark S, Magory Cohen T, Lo N, et al. (2019) Two speed invasion: assisted and intrinsic dispersal of common mynas over 150 years of colonization. Journal of Biogeography 46:45–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13473

Beesley A, Whibley A, Santure AW, Battles HT (2023) The introduction and distribution history of the common myna ( Acridotheres tristis ) in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology :1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014223.2023.2182332